It’s summer 2009. Obama is in the White House, Minecraft is released to the public, and American audiences are cozying up once again to the idea of a mockumentary.

A selection of influential mockumentaries - all of which are from various points in the 2000s

Background and the Success of the Mockumentary

I think it is clear from the selection of impactful shows above that the 2000s were a golden era for sitcoms in the format of the mockumentary. 2009 alone saw the pilots of arguably two of the most important of the genre: Parks and Recreation, and Modern Family. Both shows garnered not only critical acclaim, but also positive audience scores across the board. Clearly, something in this format works particularly well.

Having thought about this in some depth. I believe that the mockumentary format lends itself particularly well to a certain “relatable” microcosm of entertainment in which absurdist comedy meets the mundane everyday. In effect, the normal lives of supposedly normal individuals are documented - but with a twist. As it turns out, nothing about these people is normal, despite outward appearances. This, to me, supports a theory which I have had for a while - namely that life is the best writer of comedy. Who needs genius writers when life itself is so absurd as it is?

Who would’ve thought that somewhere as boring and ordinary as an office block could be the setting for a successful comedy. Surely nothing interesting could go on there - right?

Mockumentaries take this to the next level. Highlighting to the absurdity of everyday life by deliberately exacerbating the bizarre and wonderful aspects in an almost satirical fashion, thereby creating a perfect blend of relatability and insanity.

This is the niche into which sitcoms such as the aforementioned Modern Family fit. The premise of the series is, at its core, simply to follow around the everyday lives of a select family in California - that is, a select family with oddly complex social lives. The truth is, however, that many of the problems that the families face are the same as those faced by ordinary Americans daily. Of course, those problems are blown up for comedic value in the series, but the problems themselves carry over.

Luke is hospitalised due to trying to launch to space using a model rocket. Hailey has been arrested for underaged drinking and Alex has no date to the prom. Meanwhile, Claire is running around after everyone and Phil is… well… not helping. Sound like anyone you know?

The Winning Formula

While looking over the examples given above, I couldn’t help but notice that the relatability of a given series is often tied closely to how relatable the constituent characters are. Once you spot it, the winning formula becomes blindingly clear. Modern Family resonates with a lot of parents (and young people) because they see a satirised version of themself on screen. Overworked mothers see a piece of themselves in Claire, whereas boisterous man-children see a piece of themselves in Phil. Characters, it seems, and not storylines, are key.

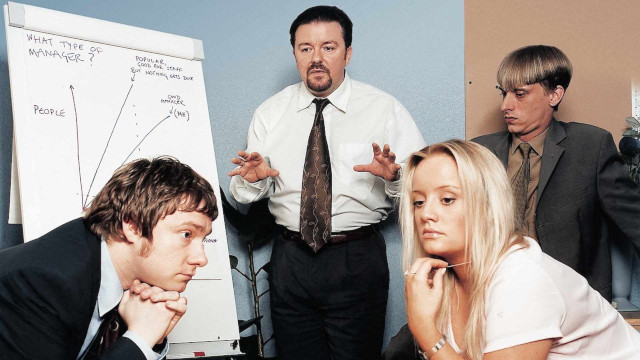

A perfect example of this effect is The Office (UK). It is often said that anybody who has worked in an office knows a David Brent and a Dawn Tinsley. Everybody has their very own Gareth Keenan and - of course - everybody sees themself as Tim

This realisation lends enormous freedom to the genre: if all a series needs to be a relatable hit is characters which the audience is capable of having an emotional connection with, the storylines can devolve into being as wacky as possible without compromising the relatability of the characters within it. I am yet to see anything which I believe truly pushes this boundary, but I can only await eagerly for somebody to try this.

That being said, I think that this means that the actual plot of many of these programs become secondary to the characters themselves. This, in turn, lends the characters themselves more to analysis than any plots which actually occur. Even considering the plot as a relevant factor, the primary driving force behind plot development is the decisions of characters as influenced by who they are. Characters are key!

Parks and Recreation

One particular example of one such mockumentary that I would like to focus on is Parks and Recreation. Premiering along with Modern Family in the summer of 2009, Parks and Recreation didn’t last quite as long, but arguably had a comparable impact.

Parks and Recreation debuted on April 9th 2009 and continued for a 7 series run until February 24th 2015

I’m focusing on Parks and Recreation in part due to the fact that I just finished it - and in part due to its genuinely diverse range of contained character tropes.

What follows is a slightly cynical but (hopefully!) accurate decomposition of each major character in Parks and Recreation.

Leslie Knope

Leslie Knope is the classic phenotype of the female overachiever. She is the type who is very good a highlighting, sticky-noting and organising her stationary. But, when push comes to shove, her deep ineptitude is laid bare. This type is very good at rote learning and memorising; they excel in school at subjects such as History and Geography which essentially boil down, at least at that level, to the memorisation of certain facts.

People like Knope are intensely outwardly defined: their self-worth and image is tied inextricably to the opinion of others. In the eyes of Knope, her public image is, quite literally, who she is. As a result, all her actions and opinions, before being put into action, are pre-filtered through a social self-defence mechanism which determines not if she desires to do something or earnestly believes something - but rather weather it is socially acceptable in this group to think or do something.

Along with this, Knope is an overzealous idealist. Despite the obvious and glaring imperfections of the world around her and the people in it, Knope continues to guard her closely held belief in “the right way” and “the proper way to do things”. This separation of attitude of hers from many of those around her gives her fantasies of heroism, frequently expressed in her belief (earnest of not) that she will one day be the first female president of the United States or “on some other little girl’s wall, like Hilary Clinton”. Possibly as a result of these delusions of grandeur, Knope vastly prefers grand, differentiating acts and gestures over calm, orderly, sensibly functioning normality - a quality, I might add, which is not ideal in any form of bureaucrat.

On the other hand, people like Knope often act with the genuine intent of doing good in the world. Weather they achieve this is secondary to their generally pure intentions.

Ann Perkins

There are some people in this world who do not know how good they had it until “it” is surreptitiously snatched from them. Ann Perkins is one of these people.

Decisions made by Perkins throughout the various series of the show indicate a clearly narcissistic character who, despite an outwardly “nice” appearance, is not afraid to cut others down to get what she wants. She has no hesitation in suddenly ending her relationship with Mark Brendanawicz because, in her words, it “didn’t feel like he was the one”. In response to Mark’s questions as to what he did wrong, no particular answer is given. While I’m not claiming that anybody who ends a relationship without some sort of deep reasoning is a sociopath, the manor and suddenness in which the long-term relationship was ended hints at a person who does not particularly care about the feelings of the other party. The break up was not any kind of mutual decision, despite amicable relations in the aftermath. Instead, it was a unilateral withdrawal. When Perkins is later treated in a similar manor by Chris (or washed up Sam Seaborn, as I like to call him), she is brought to the edge of a mental breakdown. Nobody has ever dared treat her like this before because she was in control. She was the more attractive one and was, therefore, generally more in control of relationships.

Another example can be seen in her deliberately setting Knope up with an incredibly creepy MRI technician so that she can pursue a love interest of her own with an old friend from school. It is clear that Perkins is not afraid to make decisions which hurt other people in order to get what she wants. This whole character fits very well into a sort of diluted “Mean Girl” stereotype: she is not outwardly hostile toward anybody else, but is not afraid to forcibly get people out of her way should they challenge her social dominance or control over certain situations in her life.

People like Perkins often display what I like to coin “Pack-based sociopathy”. She is seemingly capable of showing empathy and concern for members of her in-group and close friends. For those she views as outsiders, however, she is capable of being cutting and really quite cruel. When getting over her break up with Sam Se-… I mean Chris, she is perfectly happy to use various men for her own means in order to feel better. Should another woman do this in her life, she would probably encourage the behaviour, as women are seen as part of her in-group. Should a man do the same, however, and he is dragged through hell for his behaviour.

On a brighter note, people like Perkins are very often distinguished in their field due to their ability to hyper-focus and obtain goals regardless of their heavy cost. In Parkins’ specific case, she is an experienced nurse.

Ron Swanson

Ron Swanson is the inevitable conclusion of ideology. He is the caricature of an overly-principled political or religious zealot. He sticks to his principles above all, often leading to ridiculous situations, unreasonable impositions on himself or others, and conflicting goals. People like Swanson have very little care outside of achieving the goals mandated by their ideological or religious conviction, often leading to them living rather limited lives as a result.

Believe it or not, people like Swanson really do exist. A particular figure that springs to my mind is Richard Matthew Stallman - ex-chief Gnuisance of the Free Software Foundation. Famous for his stout refusal to engage with any form of non-free software, Stallman is effectively excluded from most modern technology and practically all modern software (and even hardware too, due to IME and proprietary firmware).

Figures such as Swanson and Stallman can be held in high regard by some as principled men who do not back down from a position they hold steadfastly. I, however, see them for what they are: misled fools under the false idol of ideology. The truth of life is such that no singular ideology holds the answers to all of life’s problems. Simply accepting a single viewpoint or framework as your answer to any particular problem is not the solution to being unable to make a decision or not knowing the answer. People who are unable to let go of ideology and accept that sensible concessions to principle need to be made in the real world are part of the reason that nobody can get on in the modern day.

People like Swanson and Stallman will, in addition to leading limited lives as it is, expend so much mental and physical effort in living their lives according to principle that they essentially become their own ideology. All they can talk about is their beliefs. All they think about is how best to follow their beliefs. In effect, they cease to be a person and instead become a walking belief system.

Swanson is not quite this far gone (although Stallman almost certainly is), as he still has some last vestiges of personality. For instance, he is a great enjoyer of hunting and eating vast amounts of meat - not to mention his skill in woodworking. He still has the remnants of a personality, despite his own best efforts.

Finally, Swanson and Swanson-esque people are very prone to Orwellian Doublethink. Despite being staunchly anti-government, Swanson is a bureaucrat - a position he took and mantains willingly. Despite constantly complaining about “the bloated corpse of the government” spending all his money on futile projects, he is still happy to sit and accept payment from the government budget for doing absolutely nothing at all in his job, and he is perfectly happy to employ April Ludgate to do the same.

Andy Dwyer

Dwyer fills the same role in Parks and Recreation as Homer Simpson fills in The Simpsons. He is a buffoon: harmless except in his idiocy, but without malicious intent. As a result of this, inept characters such as Dwyer are difficult to dislike.

People like Dwyer simply drift through life taking the path of least resistance to surviving on to the next day. They act essentially on an impulse cycle, reacting instinctively to stimuli without any particular forethought or planning.

More of these people exist than you would think…

This is probably a good thing, as any attempts at forethought or planning inevitably result in failure and worse outcomes compared with the usual cycle of reacting on impulse.

As a result of complete incompetence, however, Dwyer-esque figures have perpetually low standards set for them by those around them and wider society. Any and all attempts at independent thought or valid cases of initiative are praised as though revolutionary and deserving of a Nobel Prize, when, in reality, they are the bare minimum that ought to be expected of a functioning adult.

If I were to sum up Dwyer and those like him in a sentence, it would be that these people peaked in secondary school and just never grew up.

But hey, at least they peaked.

April Ludgate

Ludgate is the platonic form of the cynical, post-ironic zoomer or millenial. These people bury their true feelings underneath layer upon layer of irony until it is difficult to tell if anything they say is genuine or not. The lack of earnest in these people’s speech seeps its way into their lives, making it very difficult to take anything in their lives particularly seriously, reflecting the rampant nihilism among their generation. These are the sorts who love listening to Linkin Park and Nirvana, unaware of the fact that expressing nihilism through art is a self-refuting argument. In any case, serious argumentation is not what these kinds of people are interested in anyway, as they consider it futile to try and “wake up” anybody who isn’t on their side, instead preferring to brood over how “misunderstood” they are and how “nobody gets” them.

In effect, Ludgate represents the remnants of a generation of youths lost to technology, driven to nihilism by the world they live in, and without any particularly tangibly serious life goals or dreams.

Tom Haverford

There has never been a more fitting target for the classic /pol/-created insult of “bugman” than Tom Haverford.

Haverford possesses very little individual identity himself, preferring instead to assume the identity of those more rich and successful than himself in a futile attempt to emulate their lifestyle. Similar to Knope, he cares deeply about his image, and does not accept something as being of value until somebody significantly more powerful than him has approved of it. Throughout the show, he expresses disdain for things - that is, until his favourite magazine suddenly expresses approval, at which point he flips. Additional to this, he filters his ideas through a similar filter to Knope, except Haverford is more concerned with building his own image, whereas Knope is more simply averse to negativity.

Haverford and such characters are never particularly malicious. Instead, the best word to describe them would simply be “annoying”. Despite his less-than-endearing traits being forefront in his character, Haverford still forcefully inserts himself into social situations and gravitates toward being the centre of attention as much as possible. This only stands to worsen his annoying nature.

At the very least, he has the skills to succeed in public relations.

Jerry Gergitch

On paper, Jerry is just an average guy. On paper Jerry is an effective foil for many of the negative traits of his co-workers. Unfortunately, the world Jerry lives in is not formulated on paper, because his life is a misery.

People like Jerry are always excluded from the in-group and pushed toward being an outsider. They are not invited to events, nights out or trips. They are always overlooked when planning things and act essentially as an afterthought for when others are not available. Through no fault of his own (or barely any fault, in any case), Jerry has become what many people fear: a social ghost. Unfortunately, many of us are destined to live this way. If you take a long, hard look at yourself, I guarantee there will be a Jerry in your life who you are complicit in treating this way. In a way, Jerry could have been any of us.

On the show, Jerry’s general ineptitude at his job is often pointed to as the reason for his general isolation and maltreatment. If, however, people were to be honest about the true motivation for his exclusion, the hard truth would simply be that people do not find him interesting enough to be around. It is not an active nuisance in the way that Haverford’s presence is. But it also isn’t worth bothering about if he isn’t there for something. And so, nobody does bother.

Despite going through glaring cases of possible sociopathy, nihilism and gross general ineptitude, I think that the case of Jerry Gergitch is by far the saddest on the show.

Summary and Conclusion

I think it’s safe to say that a wide variety of aspects of society are put on full display in Parks and Recreation, which I think is quite an impressive feat for what is effectively a glorified sitcom. The accuracy of its characters to real life recurring traits is a testament to the lengths the writers went to in order to create relatable and familiar characters in a brand new environment.

It has been said that Parks and Recreation is the epitome of an Obama-era show: if only the irritating public would get out of the way as well-meaning public servants do their jobs to make the world a better place! From my perspective, this is a rather un-American attitude to display. The spirit of American constitutionalism stems from the idea that the government is not special, but is, in fact, nothing more than a service performed for the people with their consent. Politics post 9/11 moved toward a more sinister model of government - one in which the government knows what is best to protect you from the scary world out there. If you know what’s good for you, you ought to shut up and let the public servants get on with it. They know what they’re doing after all!

The politics of the show aside, I find it greatly entertaining and would highly recommend if you have some spare time!

Thanks for reading! If you agree or disagree with the analysis of one of the various characters in this article, please feel free to drop me a line to let me know your opinion. Contact information is available here.